Writer Amitav Ghosh had posted a tweet on Gladson Dungdung’s new book.

Tag Archives: adivaani

Press coverage: ‘It’s time Adivasis wrote, spoke about their anguish’

In 1980, one-year-old Gladson Dungdung and his family were displaced from their agricultural land for the construction of Kelaghat dam in Jharkhand and pushed into the forests of Simdega, where Dungdung’s father was arrested on allegations of felling trees. Ten years later, Dungdung’s parents, during another land struggle, were murdered.

In his book, ‘Whose country is it anyway?’ Dungdung writes, “The Kelaghat dam was constructed with the aim of irrigating land in Simdega block. Three villages, Bernibera, Bara Barpani, and Budhratoli, were submerged and it affected 3,500 people. Currently, the water reaches only one village — Meromdega.”

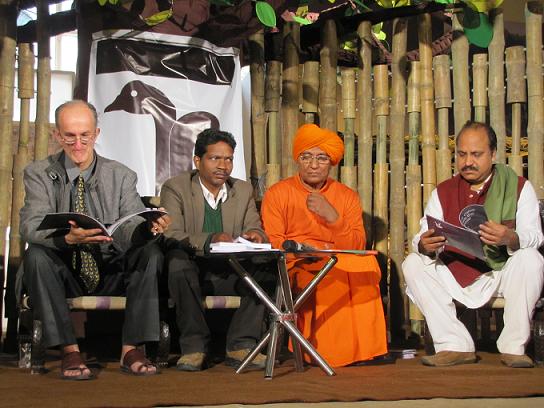

The book published by Adivaani and launched on Thursday at the Delhi World Book Fair by Himanshu Kumar, Swami Agnivesh and Felix Padel, is Gladson Dungdung’s attempt to tell the story of his people and their struggle.

Press coverage: Tribal ministers have become slaves of their seniors

Ministers who need to raise issues of tribals in Parliament “become slaves” of senior ministers and forget about the “rights of Adivasis”, Swami Agnivesh on Thursday claimed.

“All those who are elected as ministers to represent tribals in the Parliament to fight for their rights and atrocities committed upon them, themselves become slaves of big ministers and forget about the rights of Adivasis,” he said after releasing a book titled ‘Whose Country is it Anyway?’ written by Gladson Dungdung, a human rights activist of Jharkhand, at the World Book Fair here.

A review by Felix Padel On Gladson’s new book

The book’s documentation of the many forms of violence and prejudice ranged against Adivasis fills a vital gap in literature. The detail is often sickening and will make any sane person extremely angry. It is shown how Adivasis are being displaced by dams, by industrial/mining projects, by continuing tricks of non-Adivasis

Tehelka Interview with Gladson Dungdung

Video

Debate on adivasis, politics and Gladson’s new book

Our Author: A brief interview with Gladson Dungdung

Gladson Dungdung is a noted human rights activist, writer and motivator. He is not far removed from the realities of exploitation and struggles that he writes, talks and fights against. He too is a victim of displacement, who’s suffered since his childhood. His family’s agriculture land was submerged in a dam and his parents were assassinated in 1990 while dealing with the conflict of their land. He started his studies under a tree in the government run primary schools and also completed high school at Simdega, but was not able to get admission in college as he didn’t have Rs. 250. Finally, between working as a daily wage labourer and finding other means to sustain himself, he migrated, joined the land rights movement and also managed to complete his postgraduate in human rights.

He also underwent an internship in Public Advocacy from the National Centre for Advocacy Studies, Pune, where he also learnt English and did a research on the ‘Impact of forest policies on the Adivasis of Orissa’.

Though Whose country is it anyway? is his first book in English he has authored the Hindi book Ulgulan Ka Sauda, co-edited another one–Nagri Ka Nagara–and edited the Jharkhand Human Rights Report 2001-2011. He has written more than 200 articles on the issues of Indigenous People’s rights, displacement, land alienation, human rights and social change. He is pioneer in the human rights movement in Jharkhand, undertaken the fact findings of 500 cases of human rights violations. He has also trained more than 3,000 professionals on human rights including police officers, lawyers, journalists, teachers, doctors, psychiatrists, elected representatives and social activists.

He is presently working as the General Secretary of the Jharkhand Human Rights Movement and is also a member of the Assessment and Monitoring Authority in Planning Commission (Government of India).

We had this little chat with him on writing and politics, adivasis and new projects…

In your book, you thank your wife partially because she always reminds you that you have to write… why do you have to write? What’s the core function of writing in your life?

My wife is also a freelance journalist thus she not only reads my articles (Hindi) as a reader but as someone who writes. She is aware about my capacity to write, my understanding of the subject and my passion to work for and with my community. She believes that I can create impact and bring about change in the society through my writings. The writing has facilitated the exposing of discrimination, exploitation, killings, rapes, police atrocities and what not. Though writing is my passion but it has also established my name in the public domain especially because every one of my writings is based on hardcore experiences. In fact writing has changed my life.

Whose country is it anyway? is a book about abuse and resistance, but it is mostly a book depicting a historic conflict between Adivasi peoples and the upper castes and ruler classes of this country called India. Tell us, how do you envision the end of this conflict if at all?

Since, the Adivasis are the Indigenous Peoples of India therefore, they should be recognized as India’s first citizens and a special law should be enforced to that effect. The Indian State should enforce the Constitutional provisions for Adivasis, protective laws and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. If these are enforced on the ground as provisions have been made then things will definitely change.

Looking at how some groups of leftist rebels become rogues, and how the impunity of the Police and the military persists, how can one stand politically in India today? Is the Left-Right paradigm still useful as a scheme of the political scenario?

I believe that in the fight of the Left-Right the Adivasis are the losers. They have been losing their lands, forests, water, minerals and people as well (so many Adivasis are being killed in either sides of the guns and so many are behind bars). Therefore, we should resist to ending the conflict by enforcing the Indian Constitution, Laws and Policies.

If you please can write a little about your next book projects.

I have been working on two more books – one on the war for minerals and another on the how the Adivasis are being betrayed in the name of growth and development. These two books would expose the ground realities of growth, development, displacement, mining and India’s war against its own people.

Our Artist: A brief interview with Boski Jain

According to her Blogspot profile, Boski Jain is a ‘graphic designer by degree’ but she also likes ‘to illustrate too.’ Hailing from Bhopal, Boski’s career is actually more than that, and her talents go far beyond her modest declaration of craft and proficiency.

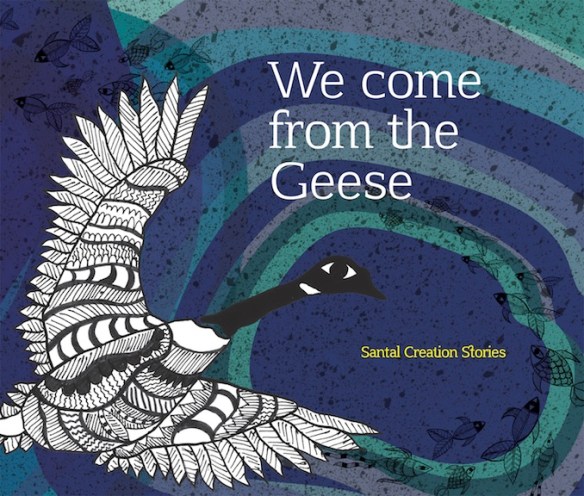

Now 24, this young artist had already published work in a collective book by Katha and has two more fully illustrated by her over the last two years (The Mistery of Blue by Tullika Books and Ek Do Dus by Eklavya.) We come from the Geese is her first of (hopefully) many works with adivaani, where she already designed our logo and was part of the process that brought us to life last year …

All the animals you create look like wonderful baroque pieces. Instead of fur, feathers, shells or scales, you come with lines, (fabric like) patterns and dots… tell us why? Is there a way to represent not only diversity but movement too?

My inspiration and ideas come from the variety of tribal arts and crafts in India, particularly the ones present in Madhya Pradesh as I have been living here and have been exposed to these more. Fabric like and block print like patterns come from them. They are bold and the perspective of the figures is simplified, hence the style can be beautifully adopted for a story for children.

Is creating illustrations with somebody else’s script difficult for you? Do you feel constrained as an artist?

I am not a writer (not so far). In my 2 years old career as an illustrator, I have only worked on scripts written by others and I have enjoyed doing so thoroughly. Picture books are picture driven hence I enjoy a certain degree of freedom.

What did you find most challenging to illustrate in the Santal Creation Stories? Why?

For me the worst and the best part about Santal creation stories is that I had never heard them before. It was the best because I got the chance to work on something unusual and hence I could use all of my imagination to visualize how the frames would look. The best part also includes working with editors who have placed their trust in me and have given me a lot of freedom. The most challenging part was to visualize and pictorially translate presence of certain supreme beings that are ‘shapeless, formless and inexplicable’, and yet make them comprehensible for children.

These stories have been carried through from generation to generation and maybe are being published as illustrated books for the first time. Hence there was also a question constantly at the back of my head about meeting the expectations of the ones who ‘own’ these and who have been narrating them for a long time.

By the way, you worked on We come from the Geese mixing digital with drawings and tint … is there a particular method to your work or is it just an intuitive way?

The method for working really depends upon each frame. Usually each element is individually worked upon by hand and then they are arranged digitally to make a composition.

Any new project coming soon?

I’m planning to work on more books for children. Also, I’d like to work on those books which do not begin with a story but begin with a piece of art that sets the stage for the story to follow.

adivaani goes to Delhi 2

Image

adivaani goes to Delhi

Santal: Announcing the launch of our first book

The art of book making is a lot like baking. The ingredients and batter for cup cakes and cakes remain the same; it’s only the mould that differs. And once the moulds have been put into the oven, it’s a matter of experience and practice that decides the outcome of the bakes. “It smells divine, but has it risen, has it cooked through?” There’s only so much one can do, the rest has to be taken in faith and hope like hell it turns out alright.

That’s how it was with our first book. First time bakers were trying their hand at catering for a wedding for 1000 invitees. The recipe we were using was of a Mexican patisserie chef. After carefully obtaining the ingredients, the process of preparing the batter started. A portion of manuscript, three parts of typing it out in a unique font, three portions of editing and proofreading, and a pinch of author intervention and we were almost ready. Choosing the mould was easy, we decided on paperback, 8 x 5 inches. While giving the batter a good mix, I started thinking of the icing, a gloss finish laminate covering maybe perfect. We were able to contact the Mexican patisserie chef for last minute advise; he said, “Don’t forget to add love, your personal touch”.

Once the mixture for the batter had been transferred to the moulds we headed to the bakery. At the bakery the baker had his apprehensions with the distinctive batter; he tasted the batter and commented on never having used our font before and he also looked strangely at the icing. Once we were able to deconstruct the font and icing for him, he seemed comfortable. But we were tense; could we do this together, in time?

Everything was ready; one didn’t want the baker not letting us load the cupcakes on the baking tray at this stage. The guests at the wedding had to be fed after all. Taking the greatest leap of faith we watched our cup cakes slide into the oven. They smelt lovely, but would they rise, would they cook through, would they burn, would they overcook, were questions running through our minds. But I guess the love we put in should more than make up for any unwarranted miscalculations. We are ready to plate up and serve. Are you ready to taste, to savor and to relish? Bon Appétit!

About Santal

This book walks us through the entity of the Santals as an indigenous people, their being, their lifestyle and their belief system.

An exegetical study of the creation narratives has been made and shows that the Santals are a non-idol worshipping theist people. This book explores how their ancient belief system has stood the test of time; where it struggles to retain its authenticity, where it has had to transform and how people who have embraced a mainstream religion strive to maintain a balance between the two.

Our author

Rev. Dr. Timotheas Hembrom has over 40 years of Theological teaching experience and is an ordained Priest of the Church of North India. He has taught at Chera Theological College, Cherrapunji, Bishop’s College, Kolkata, Gossner Theological College, Ranchi and The Santal Theological College, Benagaria. He’s a second generation Christian and educated Santal, and wears many hats. He’s a writer, editor, singer-musician, and songwriter. He’s been the editor of the Santali monthly magazine Jug Sirijol published by the Santali Cultural and Literary Society, Kolkata, for over 30 years, and continues writing for them. He’s had the accomplishment of recording Santali Christmas songs and Santali Christmas messages for the All India Radio for about 10 years.

This book is a reflection of his love for words and language, and what he is at the core, a Santal and a Theologian.

***

Book specs:

Language: Santali

Script: Roman Santali

ISBN 978-81-925541-0-5

Size: 8”x 5”, Paperback.

Pages: 168

Price: Rs. 160 · 5 USD (plus shipping expenses)

***

Place your requests for copies at:

Phone: 9831520400

Address:

adivaani

Tulip Apartments

29 A, Ismail Street

4th Floor

Kolkata-14

West Bengal

India

The Story Behind Our Logo

Ruby Hembrom

I believe not everyone is meant to do just one thing in life, I certainly am not. My 8 years of work experience in the Legal field, the Service Industry, the Social Development Sector and the Learning, Research, Development and Instructional Designing field bears testimony to this fact.

My education, training, skills and career define only part of who I am; my identity as a tribal, a Santal, is fundamental to my being and that completes who I am.

But is that enough? Life for me is about fulfilling one’s potential. In the many ways I’ve redefined who I am; the adivaani dream has made me come alive all over again. So what is the adivaani story?

2nd of April, 2012 found me trading four months of my life to learning a new skill. I attended a course on publishing to explore the possibilities of what I could do with my love for Language, the written word and stories. The course would just be an extension of what I was already doing.

In the first month there I met many fascinating storytellers in batch mates and resource persons from the publishing world and heard lots of stories firsthand. And two stories I heard planted an idea in my head that finally made me see why I was at the course.

Listening to Urvashi Butalia and S. Anand’s stories of what their publishing houses embodied got me thinking. While their story unfolded bit by bit I was bothered by a thought: both of them were sharing specific issue related stories through books that were important to be told, but there were some stories that still needed to be told–the Adivasi stories. Even the list of publishing experts we were to meet; had no Adivasi representation and that got me more concerned. Were we not important enough to be included or were we non-existent in the publishing world (this was not true as we do publish in our native regional languages).

I was consumed by the burning desire for ‘our’ stories to be out there. Who would tell them? Soon enough I saw I wanted to tell them. But I didn’t know how. I didn’t write and I had no plan, but all I knew was that the tribal voice had to be heard; the authentic Adivasi story had to be told.

That idea and the possibilities of what could happen through it filled my waking and sleeping hours. The more I thought and talked about it, it became clear how I had been living a half-life until then.

Next to come is the christening story. We need a name I thought; I don’t want to keep calling it an idea anymore.

In a mock exercise at the school we were to draw up publishing house ideas and I absolutely loved the name ‘Inkdia’ and the logo that one team came up with. So I walk up to the leader of the team, Shyamal, and ask him if the name is copy right, ‘yes’, he says. Shyamal directs me to Luis, who coined ‘Inkdia’ and designed the logo, with whom until then I had not had a real conversation. I shared my idea with him and won over a collaborator. He said he’d help with the logo, and that was just the start of his additions to my big idea. Soon we has Boski on board to work with the logo and our first few illustrated books. I was fortunate to have found my best collaborators in the course.

But I still didn’t have a name.

A little dejected I sit through the session, toying with ideas for names. I try playing around with letters around the word tribal and Adivasi and Voilá! the name as if by magic appears: adivaani, the Adivasi voice.

That’s how an idea became adivaani and adivaani became the fuel that keeps the dreamer and storyteller in me alive.

Who is adivaani

Ruby Hembrom

I believe not everyone is meant to do just one thing in life, I certainly am not. My 8 years of work experience in the Legal field, the Service Industry, the Social Development Sector and the Learning, Research, Development and Instructional Designing field bears testimony to this fact.

My education, training, skills and career define only part of who I am; my identity as a tribal, a Santal, is fundamental to my being and that completes who I am.

But is that enough? Life for me is about fulfilling one’s potential. In the many ways I’ve redefined who I am; the adivaani dream has made me come alive all over again. So what is the adivaani story?

2nd of April, 2012 found me trading four months of my life to learning a new skill. I attended a course on publishing to explore the possibilities of what I could do with my love for Language, the written word and stories. The course would just be an extension of what I was already doing.

In the first month there I met many fascinating storytellers in batch mates, school officials and resource persons from the publishing world and heard lots of stories firsthand. And two stories I heard planted an idea in my head that finally made me see why I was at the school.

Listening to Urvashi Butalia and S. Anand’s stories of what their publishing houses embodied got me thinking. While their story unfolded bit by bit I was bothered by a thought: both of them were sharing specific issue related stories through books that were important to be told, but there were some stories that still needed to be told–the Adivasi stories–and nobody was telling them. I was consumed by the burning desire for ‘our’ stories to be out there. Who would tell them? Soon enough I saw I wanted to tell them. But I didn’t know how. I didn’t write and I had no plan, but all I knew was that the tribal voice had to be heard; the authentic Adivasi story had to be told.

Two days of living with that idea, and going over the possibilities of what could happen all alone drove me crazy; I couldn’t contain the excitement any longer. 5th April, 2012, Good Friday, while getting dressed for Church, I make a phone call to Joy, my sounding board; and started the conversation in a way he was all too familiar with, “I have an idea”. That was it. No ‘not again’ reactions from him.

The more I thought about it and Joy and I talked about it, it became clear how we had been living halve-lives until then.

Next to come is the christening story. We need a name I thought; I don’t want to keep calling it an idea anymore.

In a mock exercise at the school we were to draw up publishing house ideas and I absolutely loved the name ‘Inkdia’ and the logo that one team came up with. So I walk up to the leader of the team, Shyamal, and ask him if the name is copy right, ‘yes’, he says. Shyamal directs me to Luis, who coined ‘Inkdia’ and designed the logo, with whom until then I had not had a real conversation. I shared my idea with him and won over a collaborator. He said he’d help with the logo, and that was just the start of his additions to my big idea.

But I still didn’t have a name.

A little dejected I sit through the session, toying with ideas for names. I try playing around with letters around the word tribal and Adivasi and Voilá! the name as if by magic appears: adivaani, the Adivasi voice.

That’s how an idea became adivaani and adivaani became the fuel that keeps the dreamer and storyteller in me alive.

Luis A. Gómez

I write, I design and sometimes I publish books. I’ve been a journalist for the last 25 years, and during my career I’ve had the privilege to work for/by/within the peoples in Latin America; particularly in Mexico–my motherland–and Bolivia, where I lived for 13 years. There, adopted by the Aymara people, I wrote a book about their community traditions and how they deployed them in warfare to win an insurrection in October 2003: It’s been the joy of my life to love hope, emancipation, and some other tender words, like solidarity and reciprocity.

Some day in March, 2012, I landed in Kolkata. Here, when Ruby asked me to help her in developing this idea she had and had shared with her friend Joy, my heart throbbed again. And I jumped into it: how electrifying was the prospect of using my hands and voice to create an independent press 100 percent Santali (yes, I would be grateful if along the way you call me one of you as well.) You know, I write and make books, mostly, because I love to chase dreams…

Come join us…

Boski Jain

A graphic designer by education—but that’s just one way of pegging her creative talent which is extraordinary and limitless; never ceasing to amaze. Her contribution to adivaani goes beyond the beautiful logo, the very artistic illustrated Santal Creation Stories series and every special project she undertakes for us. She’s adivaani’s pillar of innovation and ingenuity.

(A note by Ruby Hembrom from March, 2014)

About adivaani

Johar.

India is home to more than 84 million ‘Indigenous’ Peoples. Now, that’s an impressive figure and many a tribal would be overwhelmed by that number. But what else is known about us? An entry on the internet or a read in a book would throw up a stereotypical romanticized tribal lifestyle. More often than not we wonder if that is who we really are, is all that’s written about us really true.

Adivasis have a distinct socio-political and cultural identity that makes them unique as a self-sufficient community. Adivasi music, songs and dances have only been limited to the opening and closing ceremonies of government and civil society functions in schools, hospitals, colleges etc.

The history of Adivasi struggles and culture has always been written by others, i.e. by the mainstream historians. They have largely manipulated, ignored and even neglected the contributions of the Adivasi heroes in the freedom struggle of India.

The Adivasis hold on to their cultural and historical heritage with great pride, however no documentation of this rich legacy has been made by themselves.

In view of the current ‘modernisation’ and industrialisation in India, it is feared that in the near future many folk, ceremonial and other ritual art forms of the Adivasis will disappear, and it won’t be incorrect to state that the traditional oral forms of storytelling is an endangered intangible culture.

adivaani is a response to this situation.

Are we content with what’s been written about us by others? What can we turn to when we want to read, know and study about authentic Adivasi culture, history, folklores, heroes and literature?

We want to create a database of Adivasi writing for and by Adivasis. We want to document the oral forms of storytelling and folklores and tell our stories of struggles, exploitation and displacement in our words.

We seek the participation of Adivasi contemporary writers, poets and researchers and anyone who feels for the Adivasi cause to help, preserve and amplify the Adivasi voice, the adivaani.